U.S. use of Colombian bases: more questions than answers

This is cross-posted from the Center for International Policy's Colombia-focused website, "Plan Colombia and Beyond."  This week, the United States is closing down its counter-drug operations at the Manta airbase on Ecuador's Pacific coast. At the same time, it has nearly completed an agreement with Colombian authorities to use several facilities in Colombia. Colombia's defense, interior and foreign relations ministers gave a press conference yesterday confirming this, after weeks of increasing speculation in the country's media. The Colombian facilities in question are:

This week, the United States is closing down its counter-drug operations at the Manta airbase on Ecuador's Pacific coast. At the same time, it has nearly completed an agreement with Colombian authorities to use several facilities in Colombia. Colombia's defense, interior and foreign relations ministers gave a press conference yesterday confirming this, after weeks of increasing speculation in the country's media. The Colombian facilities in question are:

-

Three air force bases that may host U.S. aircraft and personnel:

- Alberto Powels, on the Caribbean coast in Malambo, Atlántico (basically, attached to the Barranquilla airport), headquarters of the Colombian Air Force's 3rd Combat Command;

- Capitán Luis Fernando Gómez Niño, in Apiay, Meta roughly 100 miles southeast of Bogotá, headquarters of the Colombian Air Force's 2nd Combat Command; and

- Palanquero, in Puerto Salgar, Cundinamarca roughly 100 miles northwest of Bogotá, headquarters of the Colombian Air Force's 1st Combat Command.

-

Two naval bases that might receive more frequent visits from U.S. vessels:

- Bahía Málaga, on the Pacific coast in Valle del Cauca; and

- Cartagena, on the Caribbean coast in Bolívar.

The Colombian daily El Tiempo reports that "Colombia is also interested in seeing that presence in at least two more bases where U.S. personnel are already assigned: Larandia (Caquetá) and Tolemaida [(Tolima)]." Both are army bases. Colombian officials contend that the U.S. troops stationed at the facilities will not play combat roles or be involved in hostilities. Those at the bases will more likely be technicians, pilots, advisors and intelligence personnel. Their mission will extend beyond counter-narcotics to include "counter-terrorism" - presumably support for Colombian military operations against guerrillas. Intelligence-gathering is likely a principal role for the U.S. personnel at the bases, and El Tiempo reports that "the accord contemplates that Colombia would have access to real-time intelligence information gathered by the planes that land at the three bases." The agreement establishing the U.S. presence at the bases would probably extend for 10 years or more, and could be signed in as little as two weeks, according to El Tiempo. The Obama administration's 2010 Defense budget request [PDF] already includes $46 million to make construction improvements to the Palanquero base. Replacing Manta The new arrangement seeks to replace the U.S. presence at the Eloy Alfaro airbase in Manta, Ecuador, which is about to end as a 10-year agreement signed in 1999 [PDF] expires in November. The Manta facility was one of three that the Clinton administration set up to replace Howard Air Force Base in Panama, which closed when U.S. troops left that country in 1999. (The other two replacement facilities, which remain open, are at Comalapa, El Salvador and Aruba/Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles.) Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa, who has famously pledged to "cut off his arm" before allowing the U.S. military presence to continue, refused to renew the agreement. The U.S. facility at the Manta base, known both as a "Forward Operating Location" and a "Cooperative Security Location," has hosted flights whose mission has been limited to counter-narcotics missions (and, as needed, emergency humanitarian or search-and-rescue missions). "Counter-narcotics" was defined to exclude missions targeting Colombian armed groups, and U.S. officials have told us repeatedly over the years that missions from the Manta base only overfly the eastern Pacific Ocean seeking to detect maritime drug trafficking. The Manta Forward Operating Location consisted of 22 buildings on 27 hectares (67 acres) of the airbase, about 5 percent of the base's total territory. The buildings, Southern Command reports, "include dining and lodging facilities, office buildings, warehouses, an aircraft ramp, hangar and fire station." This zone was ceded exclusively to U.S. personnel, who under normal circumstances totaled between 200 and 300 people, most of them employees of private contractors. How will the Colombian facilities be different from Manta? We can't answer that definitively yet, since we have no access to the draft agreement and are not privy to negotiations between U.S. and Colombian officials. However, three areas of apparent, and significant, difference from Manta are:

- The number of bases, obviously.

- The ability to carry out non-drug missions.

- How separate the U.S. facilities will be from the Colombian units using the same bases. For force-protection reasons, it is likely that U.S. negotiators would prefer an arrangement similar to Manta, in which access to areas where U.S. personnel live and work is strongly restricted. It appears, though, that Colombia is seeking more control over the entry, exit and location of U.S. personnel on its bases. The nature of this arrangement is not yet clear.

What will the new, non-drug missions be? Foreign Minister Jaime Bermúdez said yesterday that "the objective is the fight against, and the end of, narcotrafficking and terrorism." Whether the mission definition will include only "terrorism" or will expand to include undefined "other" threats isn't clear. It is likely, though, that U.S. aircraft and personnel will be involved in more missions against the FARC. Intelligence operations - particularly those targeted at the FARC leadership - could increase significantly. How is this different from what U.S. military personnel are already doing in Colombia? With U.S. trainers, advisors, intelligence people and technicians already making frequent, long-term appearances at bases like Larandia, Tolemaida, Tres Esquinas (Caquetá/Putumayo), Arauca and elsewhere, what is different now? The answer is: we don't know. One obvious answer is that the sorts of anti-drug surveillance missions that were occurring in Manta, involving sophisticated aircraft like P-3 Orions and E-3 AWACS, will now be originating in Colombia. Presumably, more planes and a slightly bigger footprint will mean more far more intelligence-gathering missions over Colombia than ever before, which may bring a notable increase in intelligence gathered about guerrilla locations and movements. All of these airbases are on the other side of the Andes from the Pacific Ocean. How will the U.S. aircraft perform Manta's mission of detecting and monitoring maritime drug trafficking in the eastern Pacific?  Again, we don't know. The eastern Pacific, off the coast of South America, is a heavily used vector for getting drugs out of South America and into Central America and Mexico, as this 2005 map shows. U.S. officials claim that Manta has played a role in about two-thirds of drug seizures in that zone since 1999. The new bases do not have the same ability to cover the eastern Pacific. Will the eastern Pacific then become narcotraffickers' preferred route, with little chance of detection? No idea. Possibly. Is this constitutional in Colombia? Opponents of the base deal insist that it is not. Indeed, Article 173 of Colombia's Constitution appears to require that the Senate "permit the transit of foreign troops through the territory of the Republic." What is the immunity issue? The degree of immunity from prosecution that U.S. personnel might enjoy is, according to press reports, one of the stickiest points in the negotiations. The newsweekly Cambio explains :

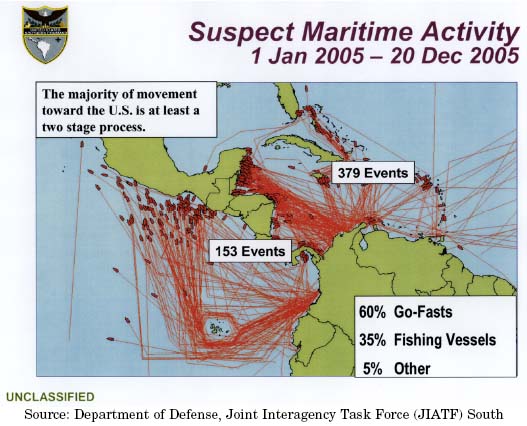

Again, we don't know. The eastern Pacific, off the coast of South America, is a heavily used vector for getting drugs out of South America and into Central America and Mexico, as this 2005 map shows. U.S. officials claim that Manta has played a role in about two-thirds of drug seizures in that zone since 1999. The new bases do not have the same ability to cover the eastern Pacific. Will the eastern Pacific then become narcotraffickers' preferred route, with little chance of detection? No idea. Possibly. Is this constitutional in Colombia? Opponents of the base deal insist that it is not. Indeed, Article 173 of Colombia's Constitution appears to require that the Senate "permit the transit of foreign troops through the territory of the Republic." What is the immunity issue? The degree of immunity from prosecution that U.S. personnel might enjoy is, according to press reports, one of the stickiest points in the negotiations. The newsweekly Cambio explains :

This discussion is not minor, and it was one of the points that justified Ecuador's decision to close Manta. That country's Constituent Assembly considered that about 300 irregular and criminal acts - illegal detentions and seizures of Ecuadorians and their goods, robberies, murders, injuries and paternity cases - are attributed to U.S. military personnel, and received no response from U.S. judicial authorities.

Should the neighbors be worried? Foreign Minister Bermúdez, today's El Espectador notes, "said that Colombia's decisions to allow operations in Colombia have no reason to affect relations with neighboring countries, since all activities will be carried out in Colombia's national territory." Colombia's neighbors, however, may not see it that way, argue critics like former Defense Minister Rafael Pardo, who said the deal is "like lending your apartment's balcony to someone from outside the block so that he can spy on your neighbors." Colombia's neighbors have seen the country nearly double the size of its armed forces in the past decade. They condemned the March 2008 incursion into Ecuadorian territory that killed top FARC leader "Raúl Reyes." And they have noted frequent accusations from top officials, particularly recently departed Defense Minister Juan Manuel Santos, alleging that the governments of Venezuela and Ecuador are actively harboring and supporting the FARC. In that environment, the addition of more military personnel from the United States will not be viewed as a regional confidence and security-building measure. To the contrary - it is more likely to add to tensions. Will this be a backdoor for U.S. military assistance? "Among [the Colombian government's] objectives is also to fill the gaps left by the eventual cutbacks in aid for Plan Colombia," noted Cambio magazine's recent cover story about the base negotiations. John Lindsay-Poland of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a U.S. advocacy group, worries that the bases will constitute an "end run" around significant cuts in U.S. military aid to Colombia since 2007. They're probably right. Base construction funding is aid. Provision of real-time intelligence is aid. An increased presence of trainers and advisors will mean more aid too. And the Colombian government may expect this show of "goodwill" to serve as leverage to prevent further cuts in U.S. military aid. However, the kind of aid that made up the bulk of prior years' packages - grants of helicopters, expensive contracts to maintain Colombia's own aircraft, aerial fumigation, and massive Special Forces training programs - will not increase as a result of the bases. What will become of the troop cap? Since 2005, the United States has operated within a limit of 800 military personnel and 600 U.S. citizen contractors who may be in Colombia at any given time. Congress required such a "troop cap" when Plan Colombia began, out of concern that Colombia's complicated conflict offered a high possibility of "mission creep." In recent years, now that U.S. personnel are not helping the Colombian security forces to set up entire new units from scratch, the U.S. presence has not approached the cap, and U.S. and Colombian officials insist that the presence at the new bases will not require an increase to the cap. It is not clear, though, whether the "troop cap" will be enshrined in the two governments' base-usage agreement, or whether it will remain simply a matter of U.S. law, which can always be changed. What happens if a Colombian military unit stationed at the same base commits human rights abuses? This is not wild speculation. For more than four years, the Colombian Air Force's 1st Combat Command, based at Palanquero, had its U.S. aid suspended because of its failure to cooperate with investigations of a 1998 indiscriminate bombing at Santo Domingo, Arauca, that killed 17 civilians. What happens if U.S. personnel at one of these bases suddenly find themselves co-located with a unit involved in a similar outrage? The answer to that question is a big "we don't know."